Summary: Neuroscientists have discovered how a small network of neurons in fruit flies accurately maintains an internal compass, challenging the theory that large networks are necessary for accuracy.

This new insight shows that small networks, when carefully interconnected, can perform complex tasks such as tracking spatial orientation. The study changes the scientific perspective on brain functions such as memory and decision-making and suggests that small brain systems are more powerful than previously thought.

Key data :

- Fruit flies use a small network of neurons to maintain a precise internal compass.

- Small networks can perform complex calculations, but require accurate connections.

- This discovery redefines our understanding of how the brain controls navigation and decision-making.

Source: HHMI

Neuroscientists had a problem.

For decades, researchers have theorized about how animal brains keep track of their position in relation to their surroundings, without external cues. It’s similar to how we know where we are, even with our eyes closed.

The theory, based on brain recordings from rats, suggests that networks of neurons, called ring attractor networks, maintain an internal compass that allows you to know where you are in the world.

It was believed that an accurate internal compass required a large network with many neurons, while a small network with few neurons would cause the compass needle to deviate and introduce errors.

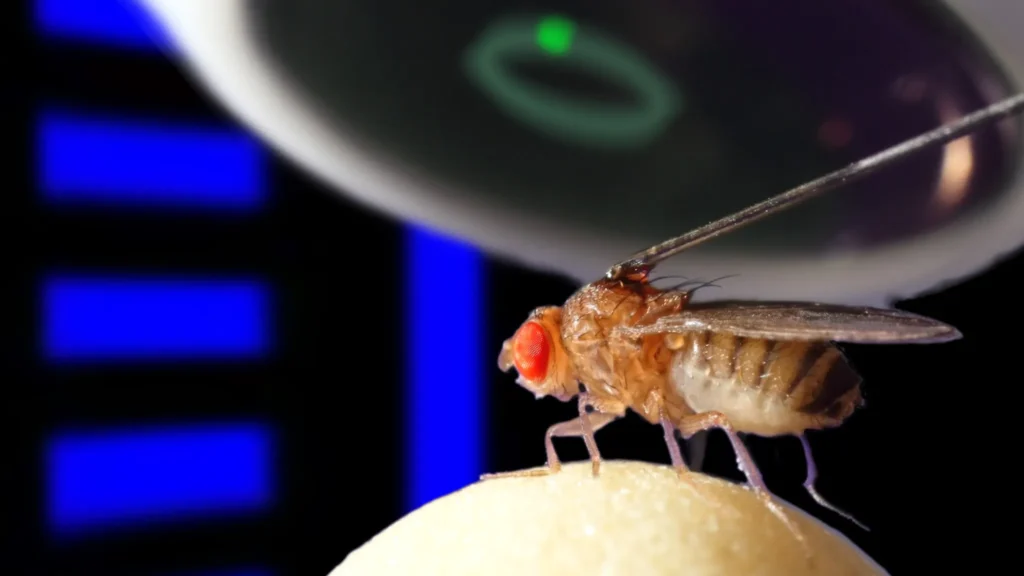

Next, researchers discovered an internal compass in the tiny fruit fly.

“The bee’s compass is very accurate, but it’s built on a very small neural network, unlike what previous theories had predicted,” says Anne Hermundstedt, leader of the Genelia group. “So there was clearly a gap in our understanding of the brain compass.”

Research led by postdoctoral researcher Marcella Normann at the Hermundstedt Laboratory at HHMI’s Genelia Research Campus explains this secret. The new theory shows how it is possible to create a perfectly accurate internal compass with a very small network, similar to that of fruit flies.

This work is changing the way neuroscientists think about how the brain performs a range of tasks, from working memory to navigation and decision-making.

“This expands our insight into the capabilities of small neural networks,” said Norman, reflecting on the surprising results of recent experiments. Researchers found that even compact models could perform intricate computations, challenging long-held assumptions about the limitations of network size.

The discovery opens new possibilities for designing efficient AI systems that require fewer resources while still delivering powerful performance. As understanding deepens, small networks may play a larger role in applications where speed, energy efficiency, and adaptability are critical.

Creation of the ring attractor

When Norman arrived on Genelia in 2019, he was faced with a problem that had long puzzled Hermundstad and others: How can the tiny brain of a fruit fly create an accurate internal compass?

A ring attractor cannot be generated from a small network of neurons , but that it is necessary to include ‘additional elements’ – such as other cell types and more detailed biophysical properties of the cells – to make it work.

To do this, he removed everything unnecessary from the existing models to see if he could make the ring attractive with what was left. He thought it wouldn’t be possible.

But Norman struggled to prove his hypothesis. Then he decided he needed a different approach.

“I had to change my thinking and think, well, maybe this is because you can create a color attraction with a small network,” he says, “and then figure out what specific conditions the network has to meet to do that.”

Modifying his hypothesis, Norman discovered that it was indeed possible to generate a ring attractor with just four neurons, provided the connections between them were carefully wired. Norman tested the new theory in the lab with other Genelia researchers and found physical evidence that the fly brain could generate a ring attractor.

“Neural networks and small brains can perform much more complex calculations than we previously thought,” Norman says. “But for that to happen, neurons must be connected much more precisely than in a large brain, where multiple neurons can perform the same calculation.”

“So there is a trade-off between the number of neurons used for this computation and the precision with which they need to be coordinated,” he says.

Next, the researchers want to investigate whether ‘additional elements’ can make the color-attracting network more robust and whether the basic calculation can serve as a building block for more complex calculations in larger networks with multiple variables.

Additional experiments could also help researchers understand how connections between neurons in the network change and how sensory signals can affect the network’s representation of head direction.

For mathematician-turned-neuroscientist Norman, it is a challenge but also a pleasure to discover how to translate biology into a solvable mathematical problem.

“The fly’s head guidance system is the first example of neural activity I’ve ever seen, so it was a lot of fun to explore and understand how it works,” he says.

About this neuroscience research news

Author: Nanci Bompey

Source: HHMI

Contact: Nanci Bompey – HHMI

Image: The image is credited to StackZone Neuro

Original Research: Open access.

“Maintaining and updating accurate internal representations of continuous variables with a handful of neurons” by Ann Hermundstad et al. Nature Neuroscience

Abstract

Maintaining and updating precise internal representations of continuous variables with a handful of neurons.

Many animals depend on stable internal representations of continuous variables—such as position, velocity, or timing—to support essential functions like working memory, navigation, and motor control. These representations allow for smooth and adaptive behavior in dynamic environments.

Traditionally, scientists believed that maintaining such precise and continuous representations required large neural networks. In contrast, smaller networks with only a few neurons were thought to produce more limited, discrete representations, lacking the resolution needed for complex tasks.

Recent analysis of two-photon calcium imaging data from fruit flies walking in darkness has revealed a striking capability: their compact head orientation system can maintain highly consistent and accurate internal representations of directional variables. This finding challenges the conventional belief that only large neural networks are capable of encoding continuous variables with precision. Traditionally, small networks were thought to produce only coarse, discrete representations due to their limited neuron count. However, the fly’s neural circuitry demonstrates that even minimal systems can achieve a level of fidelity previously considered unattainable, suggesting that biological efficiency may outpace theoretical expectations.

Building on this insight, researchers explored whether small artificial neural networks could also generate continuous internal representations. Through analytical modeling, they demonstrated that such networks can indeed be constructed to encode continuous variables, though this capability comes with trade-offs—namely, increased sensitivity to noise and variability in neuronal tuning. These findings significantly broaden the known computational potential of small networks, implying that larger networks might be able to represent a far greater number of variables and dimensions than previously assumed. This opens new avenues for designing compact, efficient neural systems in both biological research and artificial intelligence applications.