Summary: Researchers have discovered that people with Alzheimer’s disease exhibit unusually high levels of neural plasticity (the constant reorganization of brain networks), even at rest. In a large-scale study of older adults, greater neural plasticity in the visual network predicted which healthy participants would later develop dementia.

The finding suggests that measuring brain reorganization could serve as an early biomarker of Alzheimer’s risk. While the results are still experimental, they also highlight the brain’s adaptability, even in the face of disease.

Key facts

- Neuroplasticity: In Alzheimer’s patients, brain network reorganization occurs more frequently than in healthy individuals.

- Power of Prediction: High flexibility in visual networks predicted the transition to Alzheimer’s years later.

- Hope and Resilience: Despite the progression of the disease, the brain shows a dynamic adaptation.

Source: University of Michigan

Parts of the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease reorganize more frequently during rest than those without the disease, according to new research from the University of Michigan and Columbia University. In healthy people, this repeated reorganization sometimes predicts who will later develop the disease.

The brain’s ability to reorganize different areas is called neuroplasticity, says Eliana Wrings, an assistant professor at the UM School of Kinesiology and first author of the study published in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

“Our brain is constantly organizing and reorganizing regions in different functional networks to ensure they have the resources needed to perform different cognitive tasks,” said Varangis, who is also a member of the Michigan Connection Center.

“We found that the brain reorganizes itself more frequently in Alzheimer’s disease.

Our paper suggests that we could potentially use information about the way our brains are organized into functional networks to determine whether someone has Alzheimer’s.

An estimated 1 in 10 men and 1 in 5 women will develop Alzheimer’s disease in their lifetime, and early intervention is crucial to maintaining independence. Functional brain imaging has demonstrated its potential as an early biomarker of disease risk, says Wrings.

In this study, supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data while participants were awake but resting. This allowed them to examine neural plasticity in the brains of 862 older adults participating in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. These older adults were divided into three groups: cognitively normal, with mild cognitive impairment, and with Alzheimer’s disease.

Varangis and his colleagues wanted to know two things: whether brain damage from Alzheimer’s disease causes changes in neural plasticity, and whether neural plasticity can be used to predict who among a cognitively normal group will develop Alzheimer’s disease.

They found that neural plasticity was significantly greater in the Alzheimer’s group than in the cognitively normal group, across all brain regions and across six specific networks. Furthermore, neural plasticity in the visual network was significantly greater in the mild cognitive impairment group than in the cognitively normal group.

Of the 617 healthy participants at the start of the study, 8.6% developed dementia over the subsequent 11 years, which is consistent with national estimates of the prevalence of dementia in later life. Greater neural plasticity in the visual network was associated with progression to Alzheimer’s disease.

“Although this was only a modest effect, it’s a good indication that activity in these visual areas can tell us something about Alzheimer’s risk many years before formal diagnosis,” Varangis said.

“Given that we consider cognitive decline to be a core symptom of Alzheimer’s disease, finding that this sensory network predicted Alzheimer’s progression was somewhat unexpected, but not necessarily surprising.

In typical Alzheimer’s disease, the brain pathology that causes the disease only spreads to sensory areas in the later stages. These areas may exhibit greater resilience because they are among the healthiest areas of the brain that have not yet been affected by Alzheimer’s.

Varangis said the findings challenged the researchers’ intuition, as flexibility and adaptability are generally considered positive traits.

“But once we see the disease process progress, we may find that parts of the brain are no longer functioning as they should because we’re just resting and we’re reassigning brain areas to other functions over and over again,” he said.

Varangis says it’s important to remember that this is an experimental technique and certainly not for diagnostic purposes.

“The positive thing about this is that I think a lot of people think that neurodegenerative diseases are just a general slowing down of the brain over time,” he said.

“But to me, these findings also show that the brain is such a dynamic organ, that even when people experience these cognitive changes or deteriorate over time, our brains still have enough flexibility to adapt. I think it’s also a sign of hope and resilience.”

Co-authors include Jun Liu, Yuki Miao, Zhi Zhu, Yakov Stern, and Seonjo Lee, all of Columbia University.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [R01AG062578 (PI: Lee), NIH K01MH122774] and the NARSAD Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Young Investigator Grant (PI: Zhu).

About this Alzheimer’s disease research news

Author: Laura Bailey

Source: University of Michigan

Contact: Laura Bailey – University of Michigan

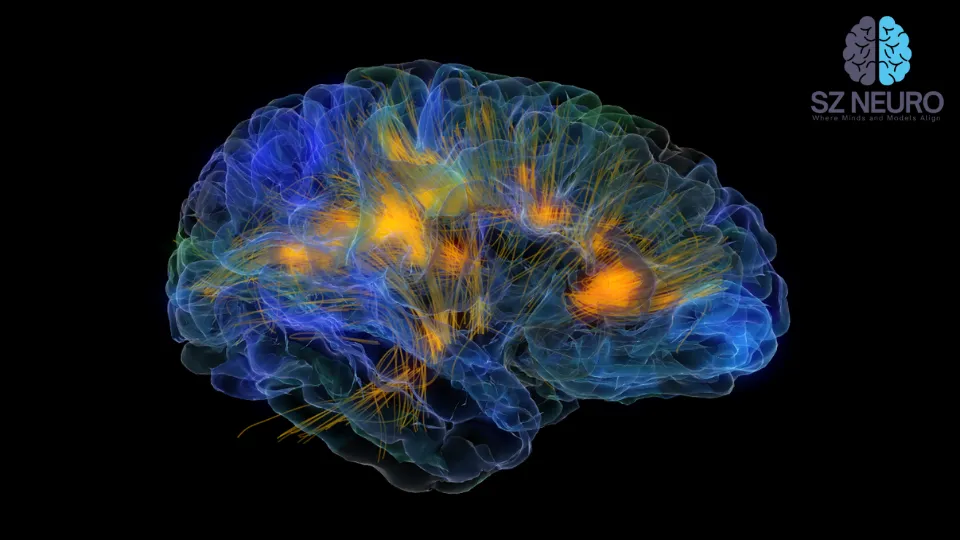

Image: The image is credited to StackZone Neuro

Original Research: Closed access.

“Neural flexibility is higher in Alzheimer’s disease and predicts Alzheimer’s disease transition” by Eleanna Varangis et al. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

Neuronal plasticity is high in Alzheimer’s disease and predicts progression to Alzheimer’s disease.

Background

Neural plasticity (NF), a measure of dynamic functional connectivity, is associated with psychiatric disorders, but has not yet been studied in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Our aim is to test whether AD is associated with changes in NF and to test its predictive value for AD change.

Method

The study included 862 older adults (461 cognitively normal [CN], 294 with mild cognitive impairment [MCI], 107 with AD) with validated resting-state fMRI data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. We defined a node’s NF as the number of times the node changed its community assignment in sliding windows, normalized by the total number of possible changes.

We calculated global NF and 12 functional network-specific NFs. We then performed separate linear mixed models on the NFs to investigate differences in these measures between our three groups. Finally, we assessed the predictive utility of NF in the transition to dementia using survival analysis.

Results

NF was significantly higher in AD than in NC in global NF (β = 0.002, 95% CI 0.001 to 0.004), and NF was significantly higher in MCI than in NC in the six networks, and NF was significantly higher in visual network than in NC. Of the n = 617 participants without dementia at baseline, n = 53 (8.6%) participants developed dementia during the follow-up visit. High NF in the visual network was positively associated with transition to AD (HR = 1.323, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.747; p = 0.049, NF per 1 SD), adjusting for age, sex, and education.

Conclusions

We found that resting NF was higher in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and predicted progression to dementia. Therefore, NF may be a valuable biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. However, further validation and mechanistic studies are needed.