Key Questions Answered

Q: How does exercise influence brain function in people with Parkinson’s?

A: Long-term cycling programs seem to alter brain activity in PD-affected regions, promoting neural reactivation and enhancing brain plasticity.

Q: What distinguishes this study from previous research?

A: This study uniquely employed implanted deep brain stimulation (DBS) devices to monitor real-time brain activity before and after exercise, providing direct evidence linking improved motor function to network-level brain changes.

Q: Did the participants experience meaningful improvements?

A: Yes. After 12 adaptive cycling sessions, participants demonstrated significant shifts in motor-related brain signals and reported noticeable enhancements in walking ability and energy levels.

Summary

Parkinson’s disease exercise” combined with deep brain stimulation (DBS) can reactivate damaged neural connections, according to groundbreaking research. A new study using second-generation DBS devices and a structured long-term dynamic cycling program has revealed measurable changes in brain activity for patients, offering hope for non-pharmacological treatment.

Researchers have found that long-term exercise programs can reactivate connections damaged by Parkinson’s disease using deep brain stimulation devices. Unlike previous studies, this study’s effort used second-generation BS devices and a long-term dynamic exercise approach to decode brain changes in people with Parkinson’s disease, along with symptoms related to symptoms.

The pilot investigation, funded by a VA Merit Award from their philanthropy at University Hospitals (Penny and Stephen Weinberg Chair Brain Bank), was led by UH and VA neurologist Asif Sheikh, MD, PhD, who is the university’s vice chairman for medical sciences and the FSOES Center, FSOES and Professionals Prajakta Shi, lead author of the article, a biomedical doctorate PhD candidate in the Sheikh lab, part of the Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center University Hospital and FES Director at Cleveland.

“We’ve already told several people that the dynamic bike is a good option for treating Parkinson’s,” the doctor said. “A recent brain study integrates deep brain stimulation with a structured exercise program to observe how consistent physical activity can reshape neural pathways over time.”

Another unique and important part of the study, Dr. Sheikh added, was the collaboration between two medical systems, which provided a large pool of subjects for recruitment purposes.

Key Facts

- Neural Adaptation: After completing 12 cycling sessions, participants exhibited notable changes in brain activity within motor control regions.

- Smart Exercise: Adaptive bikes adjusted resistance in real time, ensuring optimal participant engagement and maximizing motor benefits.

- Widespread Brain Effects: The study’s findings suggest that brain changes extend beyond the areas targeted by deep brain stimulation (DBS) implants, indicating a broader neural impact.

About The Study

“In the Parkinson’s disease trial, military veterans are required to participate in 12 dynamic cycling sessions over a four-week period.”

All aspects of the study were previously explored deep brain stimulation devices to treat their symptoms. At the same time, brain signals were measured on electrodes in it.

Another important aspect of the study is the use of adaptive wing regimen phones. This technology empowers you to find out how the patient is performing while performing.

For example, the connected game screen is set to air, riders pedal at 80 rpm and try to maintain that speed for about 30 minutes. Meanwhile, the intensity of their pedaling is displayed by an on-screen balloon, and riders have to keep the balloon above the water within specific parameters on the screen.

However, the motor vehicle’s adaptive ride uses the guesswork to apply. The bike’s motor helps achieve 80 rpm, but it also increases and decreases its resistance depending on the rider’s level of effort. The researchers believe that this push and pull mechanism is particularly effective in treating Parkinson’s symptoms.

Lara Shego, a PhD candidate at Kent State University and co-author of the study, acknowledges that 80 RPM is faster than a person naturally chooses to ride, but that it doesn’t cause as much fatigue because it helps the rider reach that level.

Interesting Results

Brain signal recordings were obtained from the implanted DBS electrodes to assess their brain signals before and after each exercise session.

“Our goal was to understand the immediate and long-term effects of exercise on the brain where the electrode is located, the site where Parkinson’s PCG is most evident,” Dr. Shego said.

The researchers did not observe immediate changes in brain signals, but after 12 sessions, they did see measurable changes in brain signals responsible for motor control and movement.

Joshi and team observed that while state-of-the-art BSS systems provide a new window into brain activity, they are limited to receiving signals only from where the electrode is recorded. As a result, other brain patterns that could contribute to the observed patterns cannot be monitored.

Key insights, Joshi explains: “It could involve a robust circuit. Exercise affects multiple upstream pathways and pathways, and it’s possible that we’re making changes at the network level that aren’t involved in motor symptoms.”

Joshi adds that further work could help provide answers.

“The good news is that our next investigation brings us closer to discovering revolutionary, personalized treatment options for Parkinson’s disease (PD).”

Patient Success

For Mandy Ensman, 59, “Parkinson’s disease exercise” reduced gait struggles and fatigue: “The bike gave me back energy I’d lost to PD.”

“I knew I needed to start exercising,” Mandy shared. “Biking helped me with several symptoms that were becoming difficult to manage. My gait improved, and I had much more energy.”

Mandy now participates in Exercise in Motion, where this study was conducted. The gym offers exercise classes and programs specifically designed for PD on computers.

Abstract

Active living in Parkinson’s disease Electrophysiologist Contact.

Objectives

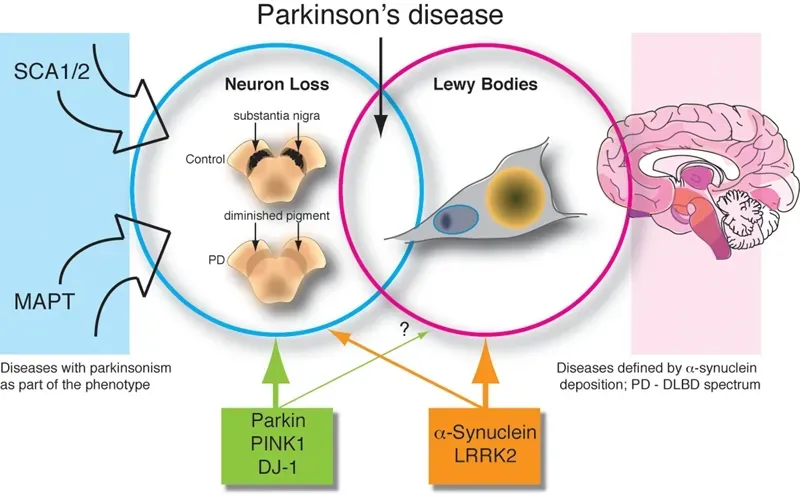

Active living as exercise holds promise for improving motor function in Parkinson’s disease (PD). We examined the underlying mechanisms of active living in PD, with an emphasis on its effects on activity in the subthalamic nucleus (STN), a key region within the basal ganglia.

Methods

The study involved 100 active cycling sessions conducted among nine individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD). Each participant completed up to 12 sessions over a four-week period.

Local field potentials (LFPs) from the subthalamic nucleus (STN) were recorded before and after testing, using deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes implanted within the nucleus accumbens.

We analyzed both the immediate and sustained effects of active cycling on LFP activity. Periodic LFP signals were evaluated by identifying the dominant spectral frequency and measuring the power at that frequency.

Concept of aperiodic LFP activity Calculating the 1/f exponent of the power spectrum.

Results

Examining the immediate and persistent effects of dynamic activity on LFPs Although not immediately significant, the long-term effects of dynamic activity on LFPs were observed in the dorsolateral region of the STN, with a logarithmic change in power and a measure of signal fluctuation, in the dorsolateral region of the STN. The ventral region of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) did not show any significant response to the exercise intervention.

Conclusion

This study proves “Parkinson’s disease exercise” isn’t just symptomatic relief—it drives cellular-level brain repair. Future work will explore personalized DBS-exercise combos. Both long-term and short-term exercise produce meaningful changes, highlighting the important role of sustained physical activity in promoting neuroplasticity and managing PD symptoms. In particular, these results demonstrate the effects of dynamic cycling on altered STN neurophysiology in PD.