Summary: Researchers have developed a brain-computer interface that can synthesize natural-sounding speech from brain activity in near real time, restoring a voice to people with severe paralysis. The system decodes signals from the motor cortex and uses AI to transform them into audible speech with minimal delay—less than one second.

Unlike previous systems, this method preserves fluency and allows for continuous speech, even generating personalized voices. This breakthrough brings scientists closer to giving people with speech loss the ability to communicate in real-time, using only their brain activity.

Key Facts:

- Near-Real-Time Speech: New BCI tech streams intelligible speech within 1 second.

- Personalized Voice: The system uses pre-injury recordings to synthesize the user’s own voice.

- Device Flexibility: Works across multiple brain-sensing technologies, including non-invasive options.

Source: UC Berkeley

Marking a breakthrough in the field of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), a team of researchers from UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco has unlocked a way to restore naturalistic speech for people with severe paralysis.

This research overcomes the long-standing challenge of latency in speech neuroprostheses—the delay between when a person tries to speak and when the sound is produced—by significantly reducing this time gap, enabling more natural, fluid, and responsive communication for users.

Using recent advances in artificial intelligence-based modeling, the researchers developed a streaming method that synthesizes brain signals into audible speech in near-real time.

As reported in Nature Neuroscience, this technology represents a major breakthrough in restoring communication for individuals who have lost their ability to speak. By translating brain activity into natural-sounding speech in near real time, it bridges the gap between thought and voice. This advance could significantly improve quality of life for people with severe speech impairments. It also lays the foundation for future innovations in brain-computer interface technology.

The study is supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) of the National Institutes of Health.

“Our streaming approach brings the rapid speech decoding capabilities of devices like Alexa and Siri to neuroprostheses,” said Gopala Anumanchipalli, Robert E. and Beverly A. Brooks Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences at UC Berkeley and co-principal investigator of the study. He explained that by using a similar type of algorithm, the team was able to decode neural data and, for the first time, achieve near-synchronous voice streaming. The result is more naturalistic, fluent speech synthesis.”

“This new technology has tremendous potential for improving quality of life for people living with severe paralysis affecting speech,” said neurosurgeon Edward Chang, senior co-principal investigator of the study.

Chang is leading a clinical trial at UCSF focused on developing speech neuroprosthesis technology that uses high-density electrode arrays to record neural activity directly from the brain’s surface.

“It is exciting that the latest AI advances are greatly accelerating BCIs for practical real-world use in the near future.”

The researchers also showed that their approach can work well with a variety of other brain sensing interfaces, including microelectrode arrays (MEAs) in which electrodes penetrate the brain’s surface, or non-invasive recordings (sEMG) that use sensors on the face to measure muscle activity.

“By demonstrating accurate brain-to-voice synthesis on other silent-speech datasets, we proved that this technique isn’t restricted to a single type of device,” said Kaylo Littlejohn, a Ph.D. student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences and co-lead author of the study.

“The same algorithm can be used across different modalities provided a good signal is there.”

Decoding neural data into speech

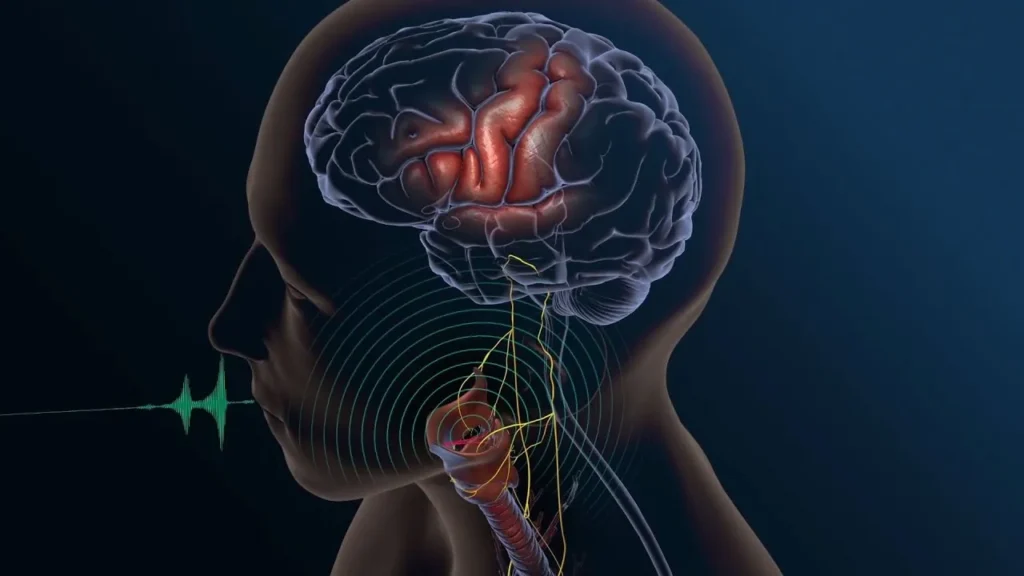

According to study co-lead author Cheol Jun Cho, UC Berkeley Ph.D. student in electrical engineering and computer sciences, the neuroprosthesis works by sampling neural data from the motor cortex, the part of the brain that controls speech production, then uses AI to decode brain function into speech.

“We are essentially intercepting signals where the thought is translated into articulation and in the middle of that motor control,” he said.

“So what we’re decoding is after a thought has happened, after we’ve decided what to say, after we’ve decided what words to use and how to move our vocal-tract muscles.”

To gather the data required to train their algorithm, the researchers asked Ann, their subject, to view a prompt on the screen—such as the phrase, “Hey, how are you?”—and then silently try to speak that sentence.

“This gave us a mapping between the chunked windows of neural activity that she generates and the target sentence that she’s trying to say, without her needing to vocalize at any point,” said Littlejohn.

Because Ann does not have any residual vocalization, the researchers did not have target audio, or output, to which they could map the neural data, the input. They solved this challenge by using AI to fill in the missing details.

“We used a pretrained text-to-speech model to generate audio and simulate a target,” said Cho. “And we also used Ann’s pre-injury voice, so when we decode the output, it sounds more like her.”

Streaming speech in near real time

In their earlier BCI study, the researchers experienced a long decoding latency, with about an eight-second delay for processing a single sentence.

With the new streaming approach, audible output can be generated in near-real time, as the subject is attempting to speak. To measure latency, the researchers used advanced speech detection methods. These methods helped them analyze brain activity patterns linked to speech. They focused on identifying the precise moment a person began trying to speak. This allowed accurate measurement of the delay in decoding speech signals. The approach provided a reliable benchmark for improving neuroprosthesis speed.

“We can see that, relative to the intent signal, the first sound is produced within one second,” said Anumanchipalli. “The device can then continuously decode speech, allowing Ann to keep speaking without interruption.”

This greater speed did not come at the cost of precision. The faster interface delivered the same high level of decoding accuracy as their previous, non-streaming approach.

“That’s promising to see,” said Littlejohn. “Previously, it was not known if intelligible speech could be streamed from the brain in real time.”

Anumanchipalli added that researchers don’t always know whether large-scale AI systems are learning and adapting, or simply pattern-matching and repeating parts of the training data. So the researchers also tested the real-time model’s ability to synthesize words that were not part of the training dataset vocabulary — in this case, 26 rare words taken from the NATO phonetic alphabet, such as “Alpha,” “Bravo,” “Charlie” and so on.

“We wanted to see if we could generalize to the unseen words and really decode Ann’s patterns of speaking,” he said.

“We found that our model does this well, which shows that it is indeed learning the building blocks of sound or voice.”

Ann, who also participated in the 2023 study, shared with researchers how her experience with the new streaming synthesis approach compared to the earlier study’s text-to-speech decoding method.

“She conveyed that streaming synthesis was a more volitionally controlled modality,” said Anumanchipalli. “Hearing her own voice in near-real time increased her sense of embodiment.”

Future directions

This latest work brings researchers a step closer to achieving naturalistic speech with BCI devices, while laying the groundwork for future advances.

“This proof-of-concept framework is quite a breakthrough,” said Cho. “We are optimistic that we can now make advances at every level. On the engineering side, for example, we will continue to push the algorithm to see how we can generate speech better and faster.”

The researchers also remain focused on building expressivity into the output voice to reflect the changes in tone, pitch or loudness that occur during speech, such as when someone is excited.

“That’s ongoing work, to try to see how well we can actually decode these paralinguistic features from brain activity,” said Littlejohn. “This is a longstanding problem even in classical audio synthesis fields and would bridge the gap to full and complete naturalism.”

Funding: In addition to the NIDCD, support for this research was provided by the Japan Science and Technology Agency’s Moonshot Research and Development Program, the Joan and Sandy Weill Foundation, Susan and Bill Oberndorf, Ron Conway, Graham and Christina Spencer, the William K. Bowes, Jr. Foundation, the Rose Hills Innovator and UC Noyce Investigator programs, and the National Science Foundation.

About this AI and BCI research news

Author: Marni Ellery

Source: UC Berkeley

Contact: Marni Ellery – UC Berkeley

Image: The image is credited to StackZone Neuro

Original Research: Closed access.

“A streaming brain-to-voice neuroprosthesis to restore naturalistic communication” by Gopala Anumanchipalli et al. Nature Neuroscience

Abstract

A streaming brain-to-voice neuroprosthesis to restore naturalistic communication

Natural spoken communication happens instantaneously. Speech delays longer than a few seconds can disrupt the natural flow of conversation. This makes it difficult for individuals with paralysis to participate in meaningful dialogue, potentially leading to feelings of isolation and frustration.

Here we used high-density surface recordings of the speech sensorimotor cortex in a clinical trial participant with severe paralysis and anarthria to drive a continuously streaming naturalistic speech synthesizer.

We designed and used deep learning recurrent neural network transducer models to achieve online large-vocabulary intelligible fluent speech synthesis personalized to the participant’s preinjury voice with neural decoding in 80-ms increments.

Offline, the models demonstrated implicit speech detection capabilities and could continuously decode speech indefinitely, enabling uninterrupted use of the decoder and further increasing speed.

Our framework also successfully generalized to other silent-speech interfaces, including single-unit recordings and electromyography.

Our findings introduce a speech-neuroprosthetic paradigm to restore naturalistic spoken communication to people with paralysis.

“This is promising to see,” Littlejohn said. “Previously, it wasn’t known whether intelligible words could be played back by the brain in real time.”

Anumanchipalli added that researchers don’t always know whether large-scale AI systems are learning and adapting, or simply pattern-matching and repeating training data. The researchers also tested synthesizing words in real time that were not part of the training data vocabulary, using 26 uncommon terms from the NATO phonetic alphabet, such as “alpha,” “bravo,” “charlie,” and others.

“We wanted to be able to generalize these words and really decode their speech patterns,” he said.

“We found that we do this well, which shows that it’s really learning the building blocks of sound.”

who also participated in the area in 2023, shared with researchers how the new streaming synthesis method could work with text-to-speech decoding to test it first.

“He explained that streaming synthesis is a more voluntarily controlled method,” Anumanchipalli said. “Hearing her voice in near real time fosters a sense of embodiment.”

Future directions

This latest move brings researchers one step closer to natural conversation with BCI data, while building on future developments.

“This conceptual framework is a significant step forward,” Cho said. “We’re optimistic that we can now make progress at every level.”

Also focusing on what the researchers say in the outgoing voice is expressive enough to reflect the tone-to-tone change in the voice, such as someone excited.

“This is work in progress, trying to see if we can decode these parallel linguistic features well from brain activity,” Littlejohn said. “This is a long-standing problem in the field of classical audio tips, and it could lead to a complete and complete cure.”

Science: In addition to the NIDCD, the research was supported by the Moonshot Science and Science Development Program for Japan and the Science Agency, the John and Sandy Wells Foundation, the Susan and Bill Oberndorff, Ron Conway, Graham Christina Spencer, the William K. Bowes, Jr. Foundation, the Rose Hills In-London Foundation, and the C. Novis Foundation National Program

Abstract

Neuroprostheses are being developed to restore natural communication to the brain’s voice.

Natural conversation occurs instantaneously. The role of having more than a few conversations in a conversation disrupts the natural flow. This makes it difficult for people with stroke to engage in meaningful dialogue, which is practically trained and emotional.

Here we used high-density surface recordings of the speech sensorimotor cortex in collaboration with clinical trials for stroke and anarthria to develop a streaming naturalistic speech synthesizer. We used a deep learning recurrent neural network transducer design and did to achieve online intelligible fluent speech of participants’ preverbal speech-specific large words with neural decoding in 80-ms increments.

Offline did implicit speech detection capabilities and can encode speech indefinitely, further increasing the coder’s uninterrupted use and speed. Our framework has also been successfully adapted to other silent speech interfaces, such as single-unit recordings and electromyography. Our findings introduce a speech neuroprosthetic paradigm to restore natural speech for people with paralysis.