Summary: A new study shows how a soft, flexible robotic hand made of silicone skin, glasses and flexible joints can handle its own grasping without the need for environmental data or complex programming. The ADAPT hand was able to grasp 24 different objects with a 93% success rate using just four programmed movements, thanks to its mechanical flexibility, which it naturally adopts.

Unlike traditional rigid robots, which require precise control, the system relies on distributed machine intelligence to mimic the adaptability of human hands. The researchers plan to integrate sensors and AI to combine the benefits of compliance with real-time feedback, thereby expanding the capabilities of robotics in human-centric environments.

Important facts:

- Self-organizing grip: The ADAPT hand achieved a 93% success rate in grasping with only 4 movement instructions.

- Machine Intelligence: The elasticity of the skin, joints, and springs allows for natural adjustments without additional feedback.

- Future integration: By combining pressure sensors and artificial intelligence, we can improve control in unpredictable environments.

Source: EPFL

When you want to lift an object, such as a bottle, you usually don’t need to know the exact position of the bottle in space to lift it successfully.

But, as EPFL researcher Kai Jonge explains, if you want to build a robot that can pick up a bottle, you need to know what’s going on around it.

“As humans, we don’t need much external information to understand something. We think it’s because of the seamless interactions that occur between an object and the human hand,” says Junge, a doctoral candidate in the School of Engineering’s Computational Robot Design and Manufacturing (CREATE) Lab.

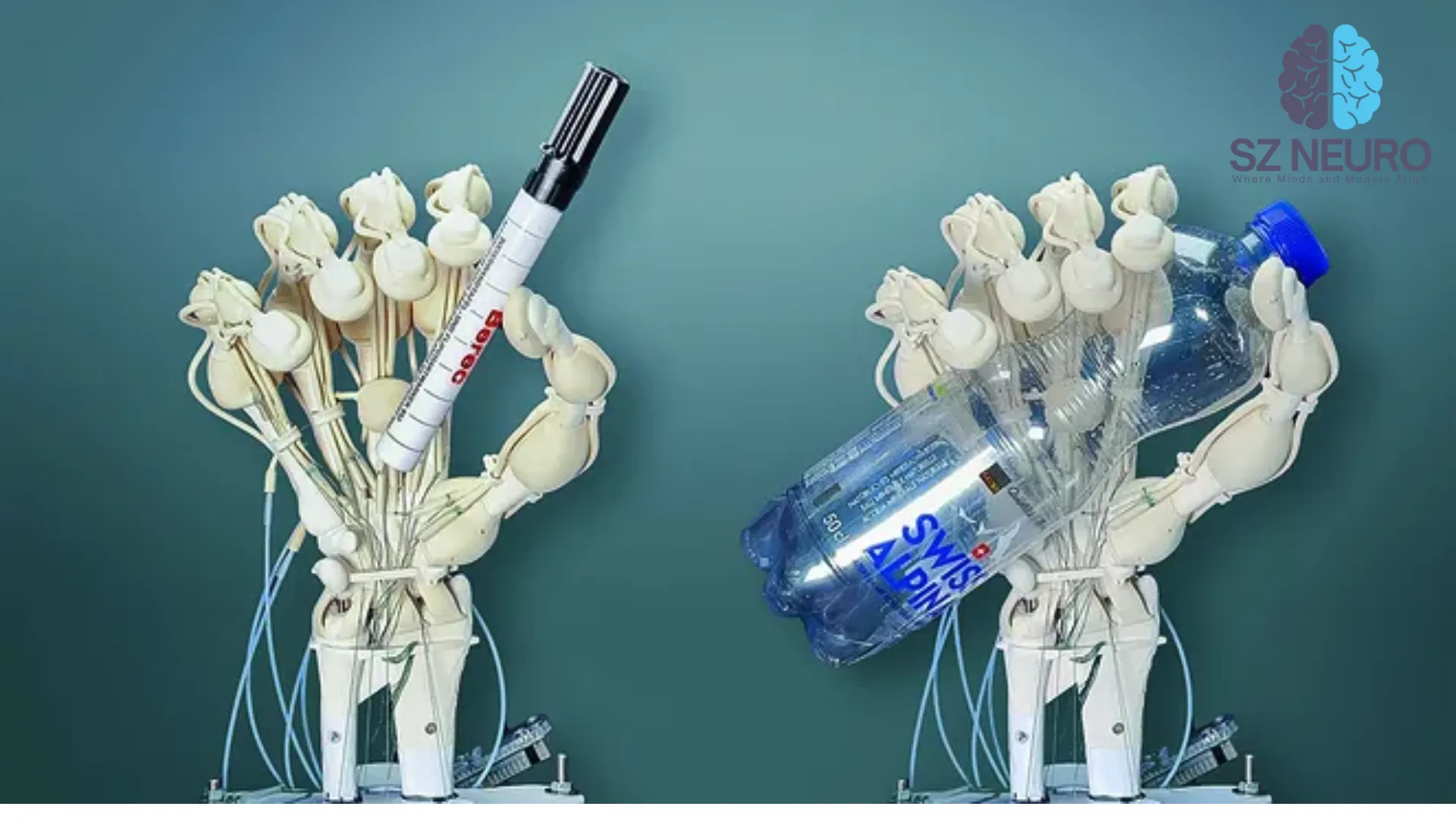

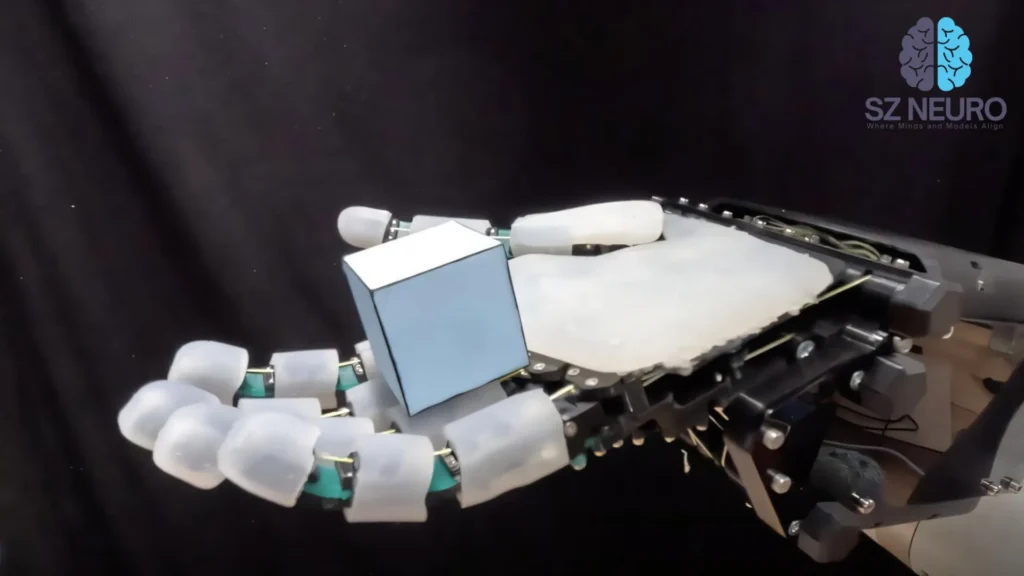

In robotics, flexible materials are materials that deform, bend, and crush. In the case of CREATE Lab’s ADAPT (Adaptive Anthropomorphic Programmable Stiffness) robotic hand, flexible materials are relatively simple: a mechanical wrist and silicone bands wrapped around the fingers, plus spring-loaded joints, combined with a flexible robotic arm.

But this strategically distributed flexibility allows the device to pick up a variety of objects using ‘self-organizing’ grips that emerge automatically rather than being programmed.

In a series of experiments, the remotely controlled ADAPT hand was able to grasp 24 objects with a 93% success rate. The hand used self-organizing grips that mimicked natural human grasping, with a 68% direct resemblance.

This research is published in Nature Communication Engineering.

Bottom-up robotic intelligence

While a traditional robotic hand requires a motor to control each joint, the ADAPT hand has just 12 motors in the wrist for its 20 joints. The rest of the mechanical control is provided by springs, which can be tightened or loosened to adjust the flexibility of the hand, and by a silicone “skin,” which can also be added or removed.

The ADAPT hand is programmed in software to move through only four common reference points or positions to pick up an object.

Any additional adjustments needed to complete the task are made without any additional programming or feedback. In robotics, this is called open-loop control. For example, once the team programmed the robot to perform a specific movement, it could adjust its grip position to accommodate a variety of objects, from a single screw to a banana.

The researchers analyzed this extreme strength (thanks to the robot’s locally distributed flexibility) with more than 300 grips and compared them to a stiffer version of the hand.

“Developing robots that can perform interactions or tasks that humans do automatically is much more difficult than most people think,” says Jung.

“That’s why we’re interested in using the distributed mechanical intelligence of different parts of the body, such as skin, muscles, and joints, rather than the top-down intelligence of the brain.”

Balancing compliance and control

Jong emphasizes that the goal of the ADAPT study was not necessarily to create a robotic hand that could grasp like a human, but rather to demonstrate for the first time how much a robot could achieve through obedience alone.

Having demonstrated this systematically, the EPFL team is taking advantage of the compliance capability by reintroducing elements of closed-loop control into the ADAPT hand, including sensory feedback—by integrating pressure sensors into the silicone skin—and artificial intelligence. This synergistic approach could lead to robots that combine the robustness of compliance under uncertainty with the precision of closed-loop control.

“A better understanding of the benefits of cooperative robots could significantly improve the integration of robotic systems in highly unpredictable environments or in environments designed for humans,” Junge summarizes.

About this robotics research news

Author: Celia Luterbacher

Source: EPFL

Contact: Celia Luterbacher – EPFL

Image: The image is credited to StackZone Neuro

Original Research: Open access.

“Spatially distributed biomimetic compliance enables robust anthropomorphic robotic manipulation” by Kai Junge et al. Communications Engineering

Abstract

Spatially distributed biomimetic compatibility enables robust anthropomorphic robotic manipulation

Humans’ impressive ability to manipulate force arises from coordinated interactions, made possible by the distributed structure and materials within the hands.

We propose that mimicking this spatially distributed compliance in an anthropomorphic robotic hand will improve the robustness of open-loop manipulation and lead to human-like behavior.

Here we introduce ADAPT Hand, equipped with configurable adaptive elements on the skin, fingers and wrist.

After quantifying the effect of individual component flexibility compared to a rigid configuration, we experimentally analyzed the performance of the entire hand.

Using automated pick-and-place tests, we demonstrated that the gripper’s robustness met the estimated geometric theoretical limit. We also subjected the robot to stress tests, performing over 800 grips.

Finally, 24 objects of different geometries were grasped in a confined environment with a 93% success rate. We show that the self-organization of the hand object, through passive adaptation, supports this robustness.

The hand shows a variety of grips depending on the geometry of objects, with a 68% similarity to the natural human grip.